On January 1st, 2012, the United States of America celebrated the new year by further enhancing its police state. MSNBC reports:

"About 40,000 state laws taking effect at the start of the new year will change rules about getting abortions in New Hampshire, learning about gays and lesbians in California, getting jobs in Alabama and even driving golf carts in Georgia.40,000 state laws, folks. The federal government is also doing its part in advancing the police state via both legislation and executive orders and mandates. But come this election season we will once again here the endless proclamations about how we are the freest nation on earth from both major American political parties. Democrats are somewhat honest when it comes to laws -they embrace them in the name of protecting the general public from various evils and fostering 'progressive' social values. Republicans love to talk about how the government that governs best governs the least and that an armed society is a polite society. On the flip side of the coin, they see the value of having a policeman, security camera and/or unmanned drone at every street corner to fight various wars, such as the 'War' on Drugs and the 'War on Terror.' In fact, neither party seems to seriously dispute the notion that this country has numerous wars to fight, in some form or another. And despite ample promises from either side about protecting certain rights of the general populace the only rights either party seems to respect are those of the multinational corporation.

"Several federal rules change with the new year, too, including a Social Security increase amounting to $450 a year for the average recipients and stiff fines up to $2,700 per offense for truckers and bus drivers caught using hand-held cellphones while driving...

"Many laws reflect the nation's concerns over immigration, the cost of government and the best way to protect and benefit young people, including regulations on sports concussions."

We Americans love to play lip service to our Founding Fathers and the revolutionary spirit of '76. But few Americans seemingly have any concept of what the emerging Americans of 1776 were and what they perceived as freedom. Quite frankly, the Americans of colonial America likely would have been horrified by the highly regulated and work driven social order that has become the norm of modern America. Likewise, modern America, especially the conservative branch, would be horrified by the uncouthness and slothfulness of early Americans. Certainly the Founding Fathers were.

"In the spring of 1777, the great men of America came to Philadelphia fr the fourth meeting of the Continental Congress, the de facto government of the rebel republic. When they stepped from their carriages onto the cobblestone streets, they could see that they were in for a very long war. New York had already been lost to the British, armies of redcoats and Hessian mercenaries were poised to cut off New England, and British plans were afoot to conquer Philadelphia and crush the rebellion. Thousands of troops in the Continental army had been lost to typhus, dysentery, smallpox, starvation, and desertion. They were outnubered an outgunned. But it was not just the military power of the kingdom that worried the leaders of the American War of Independence. There was a far more sinister and enduring enemy on the streets they walked. 'Indeed, there is one enemy, who is more formidable than famine, pestilence, and the sword,' John Adams wrote to a friend from Philadelphia in April. 'I mean the corruption which is prevalent in so many American hearts, a depravity that ism ore inconsistent with our republican governments than light is with darkness.'

"Adams was right. Many, and probably most, inhabitants of early American cities were corrupt and depraved, and the Founding Fathers knew it. Alexander Hamilton called the behaviors of Americans 'vicious' and 'vile.' Samuel Adams saw a 'torrent of vice' running through the new country. John Jay wrote of his fear that 'our conduct should confirm the tory maxim 'that men are incapable of governing themselves.' ' James Warren, the president of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts and a paymaster General of the Continental army, declared during the Revolution that Americans lived 'degenerate days.' As the war with the British thundered on, John Adams grew so disgusted at what he saw on the streets that at times he believed Americans deserved death more than freedom. Their dissolute character 'is enough to induce every Man of Sense and Virtue to abandon such an execrable Race, to their own Perdition, and if they could be ruined alone it would be just.' Adams feared that after winning independence, Americans 'will become a Spectacle of Contempt and Derision to the foolish and wicked, and of Grief and shame to the wise among Mankind, and all this in the Space of a few Years.' In September of 1777, with the British army under the command of General William Howe on the verge of conquering Philadelphia, Adams told his wife of his secret wish for America to be conquered. '[I]f it should be the Will of Heaven that our Army should be defeated, our Artillery lost, our best Generals kill'd, and Philadelphia fall into Mr. Howes Hands,... It may be for what I know be the Design of Providence that this should be the Case. Because it would only lay the Foundations of American Independence deeper, and cement them stronger. It would cure Americans of their vicious and luxurious and effeminate Appetites, Passions and Habits, a more dangerous Army to American liberty than Mr. Howes.'

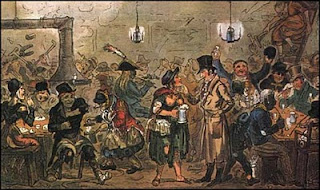

"But what the Founding Fathers called corruption, depravity, viciousness, and vice, many of us would call freedom. During the War of Independence, deference to authority was shattered, a new urban culture offered previously forbidden pleasures, and sexuality was loosened from its Puritan restraints. Nonmartial sex, including adultery and relations between whites and blacks, was rampant and unpunished. Divorces were frequent and easily obtained. Prostitutes plied their trade free of legal or moral proscriptions. Black slaves, Irish indentured servants, Native Americans, and free whites of all classes danced together in the streets. Pirates who frequented the port cities brought with them a way of life that embraced wild dances, nightlong parties, racial integration, and homosexuality. European visitors frequently commented on the 'astonishing libertinism' of early American cities. Renegades held the upper hand in Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and Charleston, and made them into the first centers of the American pleasure culture. Rarely have Americans had more fun. And never have America's leaders been less pleased by it."

(A Renegade History of the United States, Thaddeus Russell, pgs. 2-3)

Few seemingly had more fun than the backcountry settlers hailing from Ireland and the borders region of Scotland and England who eventually set down roots in Appalachia.

"...a Philadelphia Quaker named Jonathan Dickinson complained that the streets of his city were teeming with 'a swarm of people... strangers to our Laws and Customs, and even to our language.' These new immigrants dressed in outlandish ways. The men were tall and lean, with hard, weather-beaten faces. They wore felt hats, loose sackcloth shirts close-belted at the waist, baggy trousers, thick yarn stockings and wooden shoes 'shod like a horse's feet with iron.' The young women startled Quaker Philadelphia by the sensuous appearance of their full bodices, tight waists, bare legs and skirts as scandalously short as an English undershirt. The older women came ashore in long dresses of a curious cut. Some buried their faces in full-sided bonnets; others folded handkerchiefs over their heads in quaint and foreign patterns."Ah, but it wasn't simply the dress of backcountry folk that was so offensive to authorities.

(Albion's Seed, David Hacknett Fischer, pgs. 605-606)

"On the subject of sex, the backsettlers tended to be more open than were other cultures of British America. Sexual talk was free and easy in the backcountry -more so than in Puritan Massachusetts or Quaker Pennsylvania, or even Anglican Virginia. So too was sexual behavior.

"The Anglican missionary Charles Woodmason was astounded by the open sexuality of the backsettlers. 'How would the polite people of London stare, to see the Females (many very pretty)...,' he wrote. 'The young women have a most uncommon practice, which I cannot break them of. They draw their shift as tight as possible round their Breasts, and slender waists (for they are generally very finely shaped) and draw their Petticoat close to their Hips to show the fineness of their limbs -as that they might as well be in puri naturalibus -indeed nakedness is not censurable or indecent here, and they expose themselves often quite naked, without ceremony -rubbing themselves and their hair with bears' oil and tying it up behind in a bunch like the indians -being hardly one degree removed from them. In a few years I hope to bring about a reformation.'

"The backsettlers showed very little concern for sexual privacy in the design of their houses or the style of their lives. 'Nakedness is counted as nothing,' Woodmason remarked, 'as they sleep altogether in common in one room, and shift and dress openly without ceremony... children run half naked. The Indians are better clothed and lodged.' Samuel Kercheval remembered that young men adopted Indian breechclouts and leggings, cut so that 'the upper part of the thighs and part of the hips were naked. The young warrior, instead of being abashed by this nudity, was proud of his Indian-like dress,' Kercheval wrote. 'In some few places I have seen them go into places of public worship in this dress.

"Other evidence suggests that these surface impressions of backcountry sexuality had a solid foundation in fact. Rates of prenuptial pregnancy were very high in the backcountry -higher than other parts of the American colonies. In the year 1767, Woodmason calculated that 94 percent of backcountry brides whom he had married in the past year were pregnant on their wedding day, and some were 'very big' with child. He attributed this tendency to social customs in the back settlements:

Nothing more leads to this than what they call their love feasts and kiss of charity. To which feasts, celebrated at night, much liquor is privately carried, and deposited on the roads, and bye paths and places. The assignations made on Sundays at the signing clubs, are here realized. And it is no wonder that things are as they are, when many young people have three, four, five or six miles to walk home in the dark night, with convoy, thro' the woods? Or perhaps staying all night at some cabbin (as on Sunday nights) and sleeping together either doubly or promiscuously? Or a girl being mounted behind a person to be carried home, or any wheres. All this contributes to multiply subjects for the king in this frontier country, and so is wink'd at by the Magistracy and Parochial Officers."(ibid, pgs. 680-681)

Love feasts? Perhaps then the gap between 1767 and the Summer of Love isn't as wide as we have been lead to believe. What's more, it wasn't simply 'backwards' Scots-Irish staging love-ins in Colonial times. Even the rigid Puritans of New England were not immune to the animal passions of early America.

"A strange case that has rarely made it to the general histories of America is that of Thomas Morton, and his infamous Maypole at what is now Quincy, Massachusetts (not far from Salem). It was May Day, 1637... Thomas Morton decided that they should celebrate the day after 'old English custome: prepared to set up a Maypole upon the festivall day of Philip and Jacob; & therefore brewed a barrell of excellent beer, & provided a case of bottles to be spent, with other good cheer, for all comers of that day... A goodly pine tree of 80 foot long, was reared up, with a pair of buckshorns nailed on, somewhat neare unto the top of it...'

"Morton also had the assistance of the Native Americans of the vicinity, who were more than happy to join in the celebration, even though it was intended to commemorate the renaming of the area from Pasonagessit to Merry Mount. But, as Morton continues:

The setting of this Maypole was lamentable spectacle to the precise separists: that lived at New Plymouth. They termed it an Idoll, yea they called it the Calf of Horeb: and stood at defiance with the place, naming it Mount Dagon......But that wasn't the end of the story!

"Apparently, the English were taking slaves and indentured servants from Massachusetts to Virginia and selling or renting them off. Morton, in the absence of the traders, then appealed to the remaining Native Americans, slaves, and servants that they should band together and resist the efforts to expatriate them, as it were. The Maypole was the first official attempt at organizing not only a pagan festival but an armed resistance to the English officials in charge of the slave trade. In addition to welcoming Native Americans -and especially those of the female persuasion -to the feast, and 'consorting' with them and having all sorts of drunken revels, Morton trained them in the use of firearms. When an English lieutenant arrived to take charge of the rapidly deteriorating situation, he was thrown out of the settlement and evidently had to beat a retreat to England.

"Morton's experiment began to attract a lot of attention from the English authorities, as could be imagined. No less a figure than Captain Miles Standish himself -and a force comprised of eight men from 'Pascataway, Namkeake, Winismett, Weeagascusett, Netasco, and other places where any English were seated' -was sent on orders of the Governor to put down the uprising, but Standish's army was met with a force of arms by Morton's merry men.

"The resistance did not last long, however (William Bradford says that they were to drunk to effectively resist) and eventually Morton was captured and put in irons and sent to England..."

(Sinister Forces Book One, Peter Levenda, pg. 14-15)

|

| Merry Mount |

To say that alcohol was a reoccurring theme in the lives of early Americans would be something of an understatement. It was in fact a kind of national past time.

"Alcoholism was the endemic infirmity of what has been truly called 'an alcoholic republic.' When George Washington reviewed the possible commanders for the forces of the United States in the West, in 1792, he pronounced two of the five major generals alcoholic, a third, Anthony Wayne, 'whether sober or a little addicted to the bottle I know not.'"It was not merely Washington's generals addicted to the bottle. It was virtually the entire nation.

(Hidden Cities, Roger Kennedy, pg. 166)

"During the War of Independence, Americans drank an estimated 6.6 gallons of absolute alcohol per day -equivalent to 5.8 shot glasses of 80-proof liquor -for each adult fifteen or over. This is a staggering statistic, to be sure, though it likely understates beer consumption. The historian W.J. Rorabaugh has called the period of the Revolution the beginning of America's 'great alcoholic binge.'

"There was virtually no moral or legal proscription against drinking until after the War of Independence. Historians have found only a handful of prosecutions for drunkenness or unlawful behavior in taverns in colonial county records. In New York, not a single defendant was brought before the court on such charges in all of the eighteenth century. Salinger concludes that this was likely because 'magistrates did not place drunkenness high on their list of offenses warranting prosecution.' Indeed, drunkenness was often encouraged."

(A Renegade History of the United States, Thaddeus Russell, pgs. 6-7)

While MADD and various right-leaning Christian fundamentalists will be upset by these proclamations, there is ample evidence that alcohol was a much larger factor in Americans succeeding from England than numerous other more moral and philosophical reasons that are put forth by most historians. The reality is that the initial rumblings for independence, such as the Boston Tea Party of which the modern right-wing Tea Party movement is named after, were first heard in taverns. After the War of Independence the Founding Fathers were obsessed with 'positive' laws that would encourage self improvement and a more moral populace. Thus, a tax on alcohol became popular amongst the Federalist branch of the revolutionary leaders.

It was not, however, popular amongst normal Americans. In fact, it spurred an uprising that threatened to tear apart the Republic. Posterity knows this uprising as the 'Whiskey Rebellion,' which was primarily centered around western Pennsylvania.

"Though lower-class Americans continued to fill taverns, the class of men who led the Revolution were undergoing a radical self-reformation. Upper-class colonists had drunk just as heartily as their social inferiors before the War of Independence, but in the new nation, foreign visitors often commented that it was much more difficult to get a drink at an upper-class dinner party than it had been during the colonial era. American elites gave up drinking and flocked to the coffeehouses. But the people did not follow. George Washington, James Madison, and Robert Morris were among many of the Founding Fathers who supported excise taxes on alcohol after the Revolution as a means to curb drinking. Virtually all of these attempts, however, were voted down or went unenforced. The government's attempt in 1794 to enforce the national whiskey tax in western Pennsylvania resulted in what came to be called the Whiskey Rebellion, when renegades all over the region not only refused to pay up but also tarred and feathered tax collectors."Many modern historians have a rather contemptuous and dismissive view of the Whiskey Rebellion, seeing it as a minor footnote in the post-Revolutionary War years. The Founding Fathers, however, took it very seriously.

(ibid, pg. 33)

"Washington raised the largest army ever seen on American soil -larger than any force he assembled during the war for independence -to put down a rebellion in the western hills. That army, and the elaborate pageantry with which he assumed its leadership, had intended to achieve more than collecting taxes and preventing further tar-and-feathering of tax collectors. With Alexander Hamilton breathing fire at its head it was to redeem the honor of the Republic, and to hold the Ohio Valley within the Union.

"The causes and consequences of the ensuing campaign amid the tributaries of the Ohio River are buried deep in the compost of inconspicuous experience. There are no trumpet calls in its history, no famous names, no din of celebrated battles. Nor are there easy dates to remember. None the less, the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794-1795 emerges from obscurity into prominence in the American chronicle because of the fervor with which it was repressed by Washington and Hamilton. They were not stupid or lacking in breadth of vision. On the contrary, they made a correct assessment of the threat posed by the rebellion. It was possible that the Union would, in fact, come apart. Washington's presidency was focused upon preventing that outcome."

(Hidden Cities, Roger Kennedy, pg. 109)

The Founders were essentially willing to risk the succession of the West in order to impose a tax on whiskey, an important first step in establishing Federal dominance over the states. The path to our current police state was already being laid, but initially regular Americans were unmoved by the fervor that the Founders attacked their alcohol with. In fact, alcohol consumption actually increased for some time after the War of Independence despite the best efforts of vice taxes, temperance societies and the occasional military intervention.

"For a time, it appeared as if the antidrinking campaign had failed. Average annual consumption of absolute alcohol for adults rose from 5.8 gallons in 1790 to 7.1 gallons by 1810. But the fight had begun in an enduring civil war over pleasure."

(A Renegade History of the United States, Thaddeus Russell, pg. 33)

Clearly, the Revolutionary Generation was not as pure as it is commonly believed to be. Certainly, the Founding Fathers were not overly impressed. Yet the Revolutionary Generation had numerous liberties that have long since become taboo in modern American society. Recluse is not a smoker, nor a heavy drinker, yet he is constantly shocked are the increased difficulty of doing either in public (and even in private). As far back as the 1950s this would have been unheard of. Look at numerous American films from 1930s-50s when conservative moral values supposedly thrived and consider how casually actors smoke and drank from scene to scene. How often did Bogart even appear on screen without a cigarette and/or a drink? Not long ago an individual could actually go to a professional job and smoke a cigarette at their desk, which also included a flask which they took a nip out of from time to time as the day wore on.

So how then did we Americans reach the current state of affairs that we now toil under? By redefining freedom. In part two of this series we shall examine how it was done.

No comments:

Post a Comment