"Higher worlds that you uncover

Light the path you want to roam

You compare there and discover

You won't need a shell of foam

Twice born gypsies care and keep

The nowhere of their former home

They slip inside this house as they pass by

Slip inside this house as you pass by"

Welcome to the fourth installment in my ongoing examination of the legendary and pioneering psychedelic rock band the 13th Floor Elevators. During the first installment I briefly considered the group's influence and legacy as well as the psychedelic scene that began to emerge amongst University of Texas at Austin students during the very early 1960s. As was noted there it was this scene that played a key role in spawning the Elevators.

|

| the Elevators |

Thus, some sections will be more compelling after being read in conjunction with other sections. And with that disclaimer out of the way, let us move along. To start off this installment let us take a look at the group's sole out of state tour.

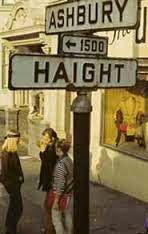

San Francisco

The Elevators hit the road for San Francisco on August 13, 1966. As was noted in part three of this series, this event was preceded by both the resolution to the drug bust the Elevators had endured earlier in the year as well as the infamous Texas Tower Sniper incident (which occurred on August 1, 1966). With the atmosphere in Texas becoming increasingly sour by the day, the group felt a change in scenery was in order. San Francisco was a logical choice on several levels.

At the time it was well on its way to becoming a major musical and general cultural center within the nation. But beyond that, expat Texans had taken an active role in establishing San Francisco's emerging psychedelic culture. What's more, several of these Texans had cut their teeth in Austin's own psychedelic scene a few years earlier and thus had some lose ties to the Elevators. The key figure was Chet Helms, a native Californian who had attended the University of Texas at Austin for a time in the early 1960s. In 1963 he famously hitchhiked back to California with his friend Janis Joplin.

As was noted in part one of this series, Helms had played a key role in establishing Austin's psychedelic. Elsewhere, part two briefly addressed the fact that Helms later became Elevator jug player/lyricist/visionary Tommy Hall's LSD connection. This resulted in Helms making regular visits to the Halls' residence in Austin during the mid-1960s. While this was going on Helms was making quite a name for himself in San Francisco.

These concerts were a big success and would lead to the rise of the famous ballrooms that would become such a key part of San Francisco's psychedelic scene.

Chet Helms claims to have been the individual who introduced strobe lights at concerts. He was much revered amongst the San Francisco crowd for his generosity. This would contribute to his later rivalry with Bill Graham, who ran the Fillmore (the other major ballroom in San Francisco at the time) and played a key role in commercializing San Francisco's psychedelic scene.

While Graham and Helms initially tried to work together their polar opposite objectives soon led to a break and rivalry that Helms was inevitably destined to lose. The Elevators inadvertently wandered into the middle of this rivalry during their San Francisco stay when they booked shows initially at both the Fillmore and Longshoremen's Hall (which at the time was being used by Helms and the Family Dog). Graham believed that he had secured an exclusive contract with the Elevators and was furious when they booked additional shows with Helms' people. Whether this contributed to the Elevators' struggles connecting with the San Francisco crowd is impossible to say, but they only played one show at the Fillmore and stuck to Helms' ballroom afterwards.

The Roky Erickson documentary You're Gonna Miss Me would have audiences believe that the Elevators all but invented the "San Francisco sound" when they rolled into town in 1966. This is utter nonsense. While reports vary, the general census is that San Francisco-ites simply didn't know what to make of the Elevators. They came into town with a Top 40 hit single ("You're Gonna Miss Me") and soon appeared on the Dick Clark's American Bandstand (their initial appearance with Dick Clark did not feature the infamous "We're all heads, Dick" line delivered by Tommy Hall, as is commonly assumed; this exchange occurred in October 1966 when the Elevators briefly returned for a follow-up appearance of Clark's show).

To San Francisco groups and fans alike, this made the Elevators come off as "pop", at least until they saw the band perform live. At that point nobody really knew what to make of the group.

Most accounts hold that the Elevators were simply to intense live, the paranoid energy of their sets bordering on punk rock nearly a decade before such a style would be recognized. Another aspect that set the Elevators apart from their San Francisco peers was their musicianship.

Accounts put forth by the likes of David McGowan and Jan Irvin alleging that the entire California rock 'n' roll scene of the 1960s was a creation of the CIA are quick to harp on the fact that most California bands were mediocre musicians. This was especially true of the L.A.-based bands of formed the legendary Laurel Canyon scene, whose studio albums were heavy on session musicians. Many band members in these groups had only recently learned how to play their instruments when these 1960s California groups started to gain national attention and even the ones who were accomplished musicians came from folk backgrounds and thus had little experience with electric instruments. While the L.A. bands were especially shoddy in this regard, their peers in San Francisco were not much better.

The Elevators had no such problems. Guitarists Roky Erickson and Stacy Sutherland, despite being quite young when the band was formed, had both taken up the guitar around the age of ten and had nearly a decade of experience under their collective belts by the time 1966 rolled around. What's more, while Austin's folk scene had inspired the Elevators to a certain extent, the primary musical influences on Erickson and Sutherland were fellow Texans like Buddy Holly and the Big Bopper and other early rock 'n' rollers who made heavy use of electric guitars. Thus, they were unburdened by transitioning to electric instruments either.

While the rhythm section at this point (John Ike Walton and Ronnie Leatherman) was not as strong as it would later be with the two Dannys (bassist Danny Galindo and drummer Danny Thomas, that is), Walton and Leatherman were solid if unspectacular and also had several years of experience on their instruments. The only Elevator who had just learned an instrument was Tommy Hall. While his jug remains one of then most controversial aspects of the band's sound, Hall had an excellent sense of rhythm and was able to effectively work the jug into their live sets. What's more, the sounds Hall generated with the jug also pre-dated some of the early synthesizers and may have influenced groups who soon began incorporating the new technology.

By all accounts, the musical prowess of the Elevators in relation to their San Francisco counterparts was unquestioned. Houston White, an associate of the Elevators, was especially contemptuous of the San Francisco bands when describing their skills in relation to the Elevators:

Ironically the Elevators, who first gained their devoted local following in no small part due their prowess as a live band, did not begin to slip as musicians until after the group's adventure in San Francisco. While part of this was due to the outfit's excessive drug use, another contributing factor was Erickson and Hall adopting the San Francisco ethos of not practicing their instruments. Still, Sutherland and the later, highly professional rhythm section of the two Dannys ensured that the band remained an effective live band for much of their run. So while the Elevators were many things, they certainly did not suffer from lack of musical ability as did many of their contemporaries during this time frame.

The Elevators themselves, or at least Tommy Hall, share a degree of the blame for their failures as well. Still, there's no denying that IA had some curious business practices. While Leland Rogers has taken a fair degree of blame over the years for the label's ineptitude, he is in fact likely the only reason why IA artists got any national exposure at all. It was the actual owners of IA whose actions were so bizarre.

IA was originally founded by a local musician to attract big label interest in his band. Upon accomplishing this goal, the label was sold to a conglomerate largely comprised of lawyers with no experience whatever in the music industry.

Shortly after the Elevators signed with IA in the 1966, Leland Rogers became the label's "national promotion man." Rogers already had nation wide contacts among DJs and other radio people and was thus able to generate a fair amount of radio play for "You're Gonna Miss Me." There are even some reports Leland was able to generate interest from Hanna-Barbera in terms of leasing the single, but these accounts are hazy and widely disputed.

The details surround the Elevators signing with International Artists are also curious as well. As one might expect, LSD was involved.

While Tommy would continue to insist that Ginther was "in the fold", the Houston attorney noted in a 1973 interview that "there was the MESSAGE, which at the time I truthfully didn't even know what they were talking about." Tommy, however, would continue to insist that Ginther had seen the light through the rest of the Elevators' run.

Despite the initial success of "You're Gonna Miss Me", problems with IA began to emerge in late 1966 when the Elevators released their follow up single, "Reverberation," and their debut LP, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators. Both were a disaster.

Emma Walton, the mother of original Elevators' drummer John Ike Walton and the initial financial patron of the band (as noted in part two, the Walton family had made money in the oil industry), began to investigate what the label was doing with the group. Her attorney, Jack McClellan, began checking up on the above-mentioned East Coast tour and found that IA had made no arrangements for such a tour whatsoever. In point of fact, they only shows they continued to set up for the band were in obscure clubs within the state of Texas. This ensured that whatever national success the group achieved up this point would totally dissipate and that they would revert to little more than a regional cult act.

These actions led to a power struggle within the band.

There even allegations that the legendary label Elektra Records, which had recently signed the Doors, had shown interest in picking up the Elevators' contract during this time. While there is some question as to just how serious Elektra Records truly was, IA made no effort to peruse this interest. Thus the label, which was seemingly to afraid to promote the band, was also unwilling to get them off their hands (and potentially make a nice profit) by selling their contract to a major label.

While I've tried to avoid much conspiracy theorizing in this series, the actions of IA on the whole are truly inexplicable to the point that one is left with the distinct notion than IA was trying to suppress the band. While the label was surely incompetent on any number of levels, Ginther and Dillard displayed enough basic business sense to raise the possibility that their actions were deliberate for some reason.

Tommy Hall's actions are also curious, though possibly more rational than they are commonly claimed to be. While he may well have felt a certain kinship with Ginther after dropping LSD and listening to Dylan with the lawyer, his actions were surely also influenced by the fact that he was getting kickbacks from the label. The Waltons' attorney, Jack McClellan, examined Tommy's relationship with the label and made some interesting observations. He stated:

And yet Tommy Hall didn't seem especially bent on stardom either. What really seems to have been driving him at this point was artist control and the ability to finally pursue his vision in full. And he got these things by the end of the year when the band went about recording Easter Everywhere. With John Ike out of the band by then and Stacy Sutherland feeling the heat off another drug bust, Tommy was able to totally dominate the artist direction of that album. What's more, IA put up top dollar for the recording process, enabling the band to explore their sound much further than on their debut (though the label naturally did the initial pressings on the cheap just as they had done for The Psychedelic Sounds of..., thus ensuring the original records sounded poor).

Thus, Tommy Hall seems to have succeeded in a fashion that appealed to his sensibilities. While he may have been many things, he was able to arrange events so that he was at the helm of one of the most unique and groundbreaking rock 'n' roll albums ever recorded with Easter Everywhere.

As for John Ike, his nightmare with IA had only begun. After he left the group he would begin what would become a decades spanning legal battle to recoup some of the group's earnings. Allegedly bank rolling the band and engaging in a protracted legal battle with IA ultimately bankrupted the Walton family. John Ike would hardly be the only band member to suffer greatly, however. And on that note, let us move on our next topic.

At the time it was well on its way to becoming a major musical and general cultural center within the nation. But beyond that, expat Texans had taken an active role in establishing San Francisco's emerging psychedelic culture. What's more, several of these Texans had cut their teeth in Austin's own psychedelic scene a few years earlier and thus had some lose ties to the Elevators. The key figure was Chet Helms, a native Californian who had attended the University of Texas at Austin for a time in the early 1960s. In 1963 he famously hitchhiked back to California with his friend Janis Joplin.

|

| Joplin and Helms |

"Music happenings were a cornerstone of the cultural revival in the Haight, providing a locus around which a new community consciousness coalesced. One of the early energy-movers in the local rock scene was Chet Helms. A couple of years earlier, Helms had forsaken a futures a Baptist minister and hitchhiked from Texas with a young blues singer named Janis Joplin. Together, these two rolling stones traveled the asphalt networks of America in search of kindred spirits until they settled in the Haight. Joplin fell in with other musicians, joining what would later become Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Helms formed the Family Dog, an organization dedicated to what was then the rather novel proposition that people should be encouraged to dance at rock concerts."

(Acid Dreams, Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain, pg. 142)The legendary Family Dog was a little less innocuous than this.

"The Family Dog was a loose collective of dope dealers connected to the pre-Charlatans crowd who had run the first head shop in San Francisco from late 1964, selling an array of knick-knacks, antiques, dope pipes and rolling papers. Luria Castell wanted to use their proceeds to fund events in an attempt to legitimize the new scene. Named after the 'dog house' on Pine Street, where the standard joke was 'Oh, who does that dog belong to?' 'Oh, it's just the family dog.' They promoted a series of shows at the Longshoremen's Hall, October 16 and 24 and November 6, 1965..."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 150)

These concerts were a big success and would lead to the rise of the famous ballrooms that would become such a key part of San Francisco's psychedelic scene.

"The Family Dog dance was a huge success, and soon these concerts became a staple of the hip community. Each weekend people converged at auditoriums such as the Avalon Ballroom for all-night festivals that combined the seemingly incongruous elements of spirituality and debauch. Thoroughly stoned on grass and acid and each other, they rediscovered the crushing joy of the dance, pouring it all out in a frenzy that frequently bordered on the religious. When rock music was performed with all its potential fury, a special kind of delirium took hold. Attending such performances amounted to a total assault on the senses: the electric sound washed in visceral waves over the dancers, unleashing intense psychic energies and driving the audience further and further towards public trance. Flashing strobes, light shows, body paint, outrageous getups – it was mass environmental theater, an oblivion of limbs and minds in motion. For a brief moment outside of time these young people lived out the implications of Andre Breton's surrealist invocation: 'Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or will not be at all.'"

(Acid Dreams, Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain, pgs. 142-143)

|

| the Avalon Ballroom |

"...Acid rock, as the San Francisco sound was called, was unique not only as a genre but also as praxis. The musicians viewed themselves first and foremost as community artists, and they often played outdoors for free as a tribute to their constituency. Even when there was a cover charge, Chet Helms and the Family Dog usually waived it for friends and neighbors. People revered Helms for this, but because of his generosity he frequently lost money and could not always pay the bands.

"It was only later, when acid rock went national in the summer of 1967, that the scene began to change. Whether it was the profit motive or just the euphoric spirit of the early days was becoming harder to sustain, some of the originals felt that things were going sour. An up-and-coming rock promoter named Bill Graham was holding shows at the Fillmore auditorium and handling the biggest acts. Unlike Chet Helms, who ran his dance shows more like a church, Graham was in it strictly for the bucks. Although he refused to turn on, he was tuned in enough to see that light shows and acid rock could have mass appeal. Before long, high-powered record execs were knocking at his door."

(Acid Dreams, Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain, pg. 144)

|

| Bill Graham |

The Roky Erickson documentary You're Gonna Miss Me would have audiences believe that the Elevators all but invented the "San Francisco sound" when they rolled into town in 1966. This is utter nonsense. While reports vary, the general census is that San Francisco-ites simply didn't know what to make of the Elevators. They came into town with a Top 40 hit single ("You're Gonna Miss Me") and soon appeared on the Dick Clark's American Bandstand (their initial appearance with Dick Clark did not feature the infamous "We're all heads, Dick" line delivered by Tommy Hall, as is commonly assumed; this exchange occurred in October 1966 when the Elevators briefly returned for a follow-up appearance of Clark's show).

|

| the Elevators on American Bandstand |

"How the Elevators were perceived in San Francisco is a hard question to answer. Although they were undeniably psychedelic in their outlook, they remained outsiders in every meaning of the word. While Janis became a poster child for the hippie-chick look, the Elevators hadn't yet made any concessions to adopting hippie attire, and with the stress of the recent bust they retained much of their standoffish paranoia and didn't hang around to socialize after performances. Somehow the band failed to evolve with the San Francisco musical culture in the same way that local bands did. Instead, they locked together and took an extreme amount of acid.

"The Elevators still played an eclectic mix of rock 'n' roll and original material, which had appeased their audience back home. Unlike the San Fran bans they didn't play long, improvised jams or meandering guitar solos. The jug was either a unique invention or an unwelcome intrusion in the music. However, even if you argue that the jug was an unnecessary appendage on a rock 'n roll cover, in an original song it would be a perfectly fused, integral part. The Elevators were conceived as an electric band delivering a psychedelic mantra from the onset. While this was Tommy's chosen medium and message, many of the Californian bands had evolved from more traditional acoustic roots to electric instruments. In contrast the Grateful Dead, despite their reputation as accomplished musicians, hadn't been conceived as an amplified, electric band, and their long semi-improvised jams betrayed their bluegrass roots. John Ike, with his kit chained to his drum stool, hit the drums harder and more aggressively than any other drummer on the West Coast. If the leather strap on his custom-made size-thirteen drum pedal broke, he simply kicked the drum instead. Stacy and Ronnie barely moved, and instead menacingly flanked Roky, who twisted and screamed until his slight frame shook. They didn't speak between songs, they didn't exactly dancer put on a show; instead, they delivered a loud and uncompromising barrage of music, saturated with intense lyrics and information."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 157-159)

Most accounts hold that the Elevators were simply to intense live, the paranoid energy of their sets bordering on punk rock nearly a decade before such a style would be recognized. Another aspect that set the Elevators apart from their San Francisco peers was their musicianship.

Accounts put forth by the likes of David McGowan and Jan Irvin alleging that the entire California rock 'n' roll scene of the 1960s was a creation of the CIA are quick to harp on the fact that most California bands were mediocre musicians. This was especially true of the L.A.-based bands of formed the legendary Laurel Canyon scene, whose studio albums were heavy on session musicians. Many band members in these groups had only recently learned how to play their instruments when these 1960s California groups started to gain national attention and even the ones who were accomplished musicians came from folk backgrounds and thus had little experience with electric instruments. While the L.A. bands were especially shoddy in this regard, their peers in San Francisco were not much better.

"To Texan ears, many of the San Francisco band sounded sloppy and under-rehearsed – in particular, their old friend Janis' new band, Big Brother and the Holding Company. Even the Dead's Jerry Garcia, when questioned about Big Brother's musical ability in September 1966, acknowledged that 'those guys are pretty new electric instruments... and they still have to get used to what comes out and what doesn't come out.'"

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 159)

|

| Janis with Big Brother and the Holding Company |

While the rhythm section at this point (John Ike Walton and Ronnie Leatherman) was not as strong as it would later be with the two Dannys (bassist Danny Galindo and drummer Danny Thomas, that is), Walton and Leatherman were solid if unspectacular and also had several years of experience on their instruments. The only Elevator who had just learned an instrument was Tommy Hall. While his jug remains one of then most controversial aspects of the band's sound, Hall had an excellent sense of rhythm and was able to effectively work the jug into their live sets. What's more, the sounds Hall generated with the jug also pre-dated some of the early synthesizers and may have influenced groups who soon began incorporating the new technology.

|

| Tommy Hall |

"Those motherfuckers couldn't play, not the Elevators but everybody else, you know, the Grateful Dead were really awful and Jefferson Airplane were grim... I mean they got real good later on. They just weren't happening, and that was the thing, the Elevators were so obviously in command of their instruments and they had it together. Big Brother and the Holding Company were awful... If it hadn't been for Janis they'd have never gotten across the street."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 159)Thus, the Elevators were largely spared the indignity of session musicians on their records. They also wrote the bulk of their own material, with fellow Austin-ite Powell St. John being the only songwriter to contribute heavily to the band's albums outside of the actual members. While the Elevators did a far amount of covers while playing live (as did all bands during this era), their studio albums were largely comprised of original material written by Erickson, Sutherland and Hall.

|

| Powell St. John |

International Artists

Easily one of the strangest and least remarked upon aspects of the Elevators' brief run was their record label, International Artists (IA). While it only lasted from 1965 to 1970, the small Texas-based label would release some of the most groundbreaking psychedelia ever recorded.

"Houston's International Artists label was run by Leland Rogers, the brother of rocker-turned-country crooner Kenny Rogers (who scored his first big hit in 1968 with a transparently insincere psychedelic ditty, 'Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)'). By the end of the '60s, the company had a remarkable psychedelic roster including Lost & Found, the Golden Dawn, Bubble Puppy, and the Red Crayola, which debuted with an intriguing effort called The Parable of Arable Land, featuring a guest appearance by Erickson (though much of its music was static and self-consciously arty). International Artists signed the Elevators, but like many of their labelmates, the musician soon had a long list of complaints about the label and Leland Rogers, whose business practices helped doom them to obscurity..."

(Turn on Your Mind, Jim DeRogatis, pg. 71)

|

| several of the other legendary International Artists releases: Red Krayola's The Parable of Arable Land, Bubble Puppy's A Gathering of Promises and Golden Dawn's Power Plant |

IA was originally founded by a local musician to attract big label interest in his band. Upon accomplishing this goal, the label was sold to a conglomerate largely comprised of lawyers with no experience whatever in the music industry.

"Inspired by the name 'United Artist,' Fred Carroll had conjured up the impressive-sounding International Artists to attract major label interest for his band the Coastliners. Following local success in October 1965, 'All right/Wonderful You' was picked up by the Back Beat label and, having no further need for the International Artists name, Carroll sold it to a strange conglomerate for the $35 cost of the label printing blocks. A pair of lawyers, Bill Dillard and Noble Ginther, a music business hustler and publisher, Kendall A. Skinner, and a studio boss, Lester J. Martin – inspired by the success of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones – were eager to get into the 'lucrative' music industry. Dillard and Ginther had no previous experience whatsoever, but were convinced that if they found the Texas Beatles, they could stand to make a lot of money. Meanwhile, Skinner worked as the A&R man while Les Martin hoped new bands to pass through his 'Jones and Martin Recording Studio,' co-owned with Doyle Jones."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 135)

|

| the Coastliners |

The details surround the Elevators signing with International Artists are also curious as well. As one might expect, LSD was involved.

"While John Ike worried about the band's long-term future, Tommy was fed up with dealing with promoters and contracts, and was more concerned with preserving the essence of the band's message. He decided that if their fate was sealed with IA, then they should understand the group's perspective. Noble was a 'local boy' who a grown up with Elevators soundman Sandy Lockett in Houston. So Tommy, armed with LSD and a copy of Dylan's recently released Blonde on Blonde album, decided to pay Noble Ginther a visit. Allegedly, Tommy gave him acid and put on Dylan's 'Visions of Johanna' as proof of the high levels pop music was now entering. Ginther supposedly pleaded with him to turn it off and sat out the rest of the trip while Tommy explained his ideas. With Ginther 'converted' and 'in the know,' a contract was drawn up."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 143)

|

| Dylan's Blonde on Blonde |

|

| possibly Ginther |

"International Artist, out of a mixture of fear, ignorance or stupidity, didn't promote or distribute the single or album at all. But this was just the start of IA's incompetence. They simply didn't know how to promote a band, let alone one as unique as the Elevators. Fearful of adverse press leaking out over the bust their association with drugs, IA simply decided to do nothing. With no band photos or interviews, this was merely the beginning of what became the mystique of the Elevators. Instead, they blindly soldiered on, demanding more product in the hope that some of it would sell."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 198-199)If International Artists had been weary of promoting the Elevators at the onset, they were positively terrified after the debacle at the Houston Music Hall Theatre (discussed in part three of this series). To band members and outsiders alike, the label's behavior became increasingly bizarre after the brief California tour and went completely overboard after the Music Hall show.

"While the band and their contemporaries had done everything possible to capitalize upon their status as returning heroes, IA appeared to be antagonistically attacking their progress. While it is understandable that a company run by lawyers was fearful of promoting a bunch of drug-fueled freaks to a wider market, they were also failing to serve their own self-interest. It was almost as if the Californian tour had been a useful means to keep the band out of the way while they spun the singled to the music industry rather than to the music-buying public. The failure of the Musical Hall show further fueled IA's paranoia and lack of trust in the band. They were simply too frightened to allow the band to be seen or heard in interviews or photos, and yet used the drug situation to exploit and control them at the same time. Leland Rogers, the man solely responsible for spinning the first single, repeatedly failed despite strong material. It was still presumed he could hype the album to success via his influence on a network of DJs and promoters. However, a promotional trip to the East Coast to market the album and follow-up interest in bookings for an East Coast tour, with shows from Florida to Maryland resulted in nothing but confusion."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 224)

|

| Leland Rogers |

These actions led to a power struggle within the band.

"However, instead of the great escape, the situation degenerated into a triangular power struggle between IA, John Ike and Tommy. The dynamic between Tommy and John Ike had somehow worked until now, the two extremes being equally important in producing the band's unique persona. While Tommy felt John Ike's adverse reaction to hallucinogens was the first crack in his master plan, John Ike anchored them in the real world and help facilitate Tommy with the 'thinking' while he organize the 'doing.' However, Tommy wanted to maintain the status quo and stay with IA. He felt he had reached a level of understanding with IA by taking acid with Ginther, and this could be hard to achieve at another label. This meant he could concentrate on his ideas without becoming involved in business. Making money or repaying debts were irrelevant to his vision and, as Tommy expressed in 1973, 'the band was really just a device for our own education, so that it could pay for itself. In other words, we were just feeding back education so we could make some money, so we could makes more education...'

"The IA bosses were shrewd businessmen and did what every record label practices, divide and conquer: recognize the band's hierarchy and prey on their weaknesses. IA made further empty promises to replace equipment, book a national tour and give them more studio time for a new album. Tommy felt that a return to San Francisco would cause more problems than it solved and that by sticking with IA, which was hungry for product, he could gain increased artistic control."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pgs. 248-249)

|

| John Ike Walton |

While I've tried to avoid much conspiracy theorizing in this series, the actions of IA on the whole are truly inexplicable to the point that one is left with the distinct notion than IA was trying to suppress the band. While the label was surely incompetent on any number of levels, Ginther and Dillard displayed enough basic business sense to raise the possibility that their actions were deliberate for some reason.

Tommy Hall's actions are also curious, though possibly more rational than they are commonly claimed to be. While he may well have felt a certain kinship with Ginther after dropping LSD and listening to Dylan with the lawyer, his actions were surely also influenced by the fact that he was getting kickbacks from the label. The Waltons' attorney, Jack McClellan, examined Tommy's relationship with the label and made some interesting observations. He stated:

"God knows what they lived on. See, Tommy was able to go in there to IA and get these piddling little handouts – maybe fifty bucks to last him a couple of weeks. Totally unsatisfactory trips like that. But all seemingly cool with Tommy, since he got to buy as much acid as he wanted. What did he care about eating or paying back his debts, or that Momma Walton was out thousands? He seemed to be sold on Ginther personally, because he'd once dropped some acid with him, which shows how sophisticated Tommy was. By the time I latched on the band's bankroll, the pattern was already established. Anytime they got a couple of hundred dollars together, Tommy would fly up to San Francisco, buy a bunch of acid and fly back. I finally indulged John Ike to the extent of letting him buy a motorcycle just because I felt Tommy had appropriated so much of their bread. He wasn't hoarding it for himself, oh no! He was spending it on all of them. But you can see why John Ike insisted on managing the band, so he could protect his share. I was supposed to clean up all that shit, and what I actually did was just accelerate the process of their disintegration. All this was irrelevant to Tommy. He was willing to sell his soul for stardom; he was willing to let himself be screwed by these straight guys. John Ike wasn't; Roky didn't know."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 248)

And yet Tommy Hall didn't seem especially bent on stardom either. What really seems to have been driving him at this point was artist control and the ability to finally pursue his vision in full. And he got these things by the end of the year when the band went about recording Easter Everywhere. With John Ike out of the band by then and Stacy Sutherland feeling the heat off another drug bust, Tommy was able to totally dominate the artist direction of that album. What's more, IA put up top dollar for the recording process, enabling the band to explore their sound much further than on their debut (though the label naturally did the initial pressings on the cheap just as they had done for The Psychedelic Sounds of..., thus ensuring the original records sounded poor).

Thus, Tommy Hall seems to have succeeded in a fashion that appealed to his sensibilities. While he may have been many things, he was able to arrange events so that he was at the helm of one of the most unique and groundbreaking rock 'n' roll albums ever recorded with Easter Everywhere.

As for John Ike, his nightmare with IA had only begun. After he left the group he would begin what would become a decades spanning legal battle to recoup some of the group's earnings. Allegedly bank rolling the band and engaging in a protracted legal battle with IA ultimately bankrupted the Walton family. John Ike would hardly be the only band member to suffer greatly, however. And on that note, let us move on our next topic.

Roky Erickson's Mental Breakdown

By most accounts, Erickson's mental problems first began to manifest during the band's stay in San Francisco. In the documentary on his life, You're Gonna Miss Me, Clementine Hall (Tommy's wife) recounts how Roky first began hearing voices (a state of affairs that would continue for decades) while in 'Frisco, and that she would take him down to the beach and allow the waves to strike him until the voices subsided.

Erickson himself alleged at one point that his mental state began to change around the age of 17, prior to his discovery of LSD, but now refutes this claim. In recent years he has also taken strong issue with being diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia in general.

Much of the evidence indicates that Roky had already developed some mild psychosis prior to joining the Elevators. Predictably, this has led many to the conclusion that it was Erickson's LSD use that set him on the path of total breakdown that he later wandered. But there were other factors at play around the time (i.e. the San Francisco tour) when Roky's psychosis became overt and evident to all.

Some have speculated that a certain drug he began taking leading up to his appearance before the draft board in 1966 played a much larger role in his psychosis than LSD. Taking this substance was part of a broader plan devised by Tommy Hall to help Roky beat the draft.

Atropine is closely related to scopolamine, which is a chemical variant on the former. Both are derived from solanaceae plants such as the above-mentioned belladonna and mandrake root, which have been used in a host rituals for centuries. Scopolamine, when paired with morphine, is known to create a state known as "twilight sleep." At various times the US national security apparatus would consider the use of twilight sleep as an interrogation technique. Strangely, Roky reportedly first used heroin while in San Francisco as well. Given Tommy Hall's loathing for opiates, however, it is unlikely that their was an attempt at play to cause a similar state in Roky. But moving along.

While Roky's mental state has generally been attributed to excessive drug use, many friends and associates of the Elevators have insisted that Roky's early psychosis was largely an act. What really unhinged him was not the drugs (at least at first), but the electroshock treatment he has been subjected to over the course of his life. While many believe that Roky was only subjected to electroshock after he was sent to Rusk in 1969, his relationship with the treatment began earlier than this.

Both Tommy and Clementine Hall have insisted that after the second time Roky had taken acid they dropped him off at his house before the effects of the drug had warn off. Evelyn Erickson, Roky's mother, was understandably shocked and, according to the Halls, she immediately took him to the Austin State Hospital for treatment. Evelyn has long denied this account but Chet Helms also noted that he had encountered Roky in an institution before the Elevators began. Helms, as noted above, was a regular visitor at the Halls' house even after he moved out to California in 1963. Clementine Hall has gone even further with her claims, stating:

If this account is true, it should certainly be factored in to Erickson's breakdown. Roky was also institutionalized briefly while he was in San Francisco as well (in both cases, and in many others, Tommy Hall came to break Roky out) and while there were plans to give him electroshock therapy then, they apparently fell through. Upon returning to Texas from San Francisco, Roky began to seek out psychiatric help in order to thwart the draft board. At this point he seems to have gained a most curious patron who would protect him for a time.

As was noted in part two, its also possible Chet Helms had ties to the Millbrook scene. Thus, Roky's relationship with Hermon was potentially either the first or second brush the Elevators had with the Millbrook people. This is especially relevant to the fate of Tommy Hall, as we shall see in the next installment, but it should be noted that I have not been able to determine if Hermon had yet made contact with the Millbrook clique when he first encountered Erickson.

Unfortunately, Drummond doesn't really explain what other rescue Hermon performed for Roky. He is only mentioned once more in Eye Mind, in a quote from Evelyn Erickson recounting Roky's legal woes in 1968 (which resulted in him being subjected to electroshock treatment in a Houston psychiatric hospital for a brief time as well). Apparently many of the local psychiatrists wanted to subject Roky to a more "intense" regiment of treatments, but Hermon briefly protected him. There relationship seems to have ended after Roky was living with one of Hermon's nurses for a week or so, and then simply walked away. Its possible Hermon's own legal woes also led to his break with Erickson (and Austin on the whole) as well.

Roky's luck was about to come to an end, and he was finally subjected to heavy electroshock therapy shortly after the Elevators dissolved. He was not the only member that would receive such treatments either. These and other fates shall be considered in the final installment of this series. Stay tuned.

Erickson himself alleged at one point that his mental state began to change around the age of 17, prior to his discovery of LSD, but now refutes this claim. In recent years he has also taken strong issue with being diagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia in general.

"... There has been much debate over the years as to when Roky first experienced the symptoms of mental illness and what the root of the cause was. He has been diagnosed as schizophrenic on several occasions, and here lies the problem. As of 2007, Roky will clearly tell you he has never experienced any symptoms of schizophrenia – it was all a necessary ruse to avoid the draft board in 1966 and jail in 1969. 'Schizophrenia' is an unsatisfactory umbrella term for a range of disorders for which there is no medical diagnosis, and the stigma can lead to marginalization and social control, often through excessive medication and incarceration – both of which he experience. Today there is a serious lobby by many psychiatrists to argue that schizophrenia is a redundant and unhelpful diagnosis. Certainly Roky has a highly emotional state of being, informed from an early age by his equally neurotic parents, which manifested in a hysterical and eccentric personality. In 1973, Rocky stated he became aware of his mental condition changing age seventeen (he now refutes this). Aged eighteen onwards he embarked on the toxic overload, experimenting with a pharmacopoeia of illicit substances, supposedly typical 40% of people suffering from 'schizophrenia.' In 1975, Roky surmised that although bands took drugs to keep on the road he used mine-altering substances as a means of retaining control of his mind.

"From an early age, Roky made a decision to live his life on his own terms. He invariably stops taking the anti-psychotic medication he has been prescribed as soon as the symptoms begin to be controlled, preferring his natural mental state to the inhibiting side effects. Roky's use of drugs and chosen lifestyle were both therapeutic and destructive to his mental state. Roky's behavior during his periods of illness appear to parallel many of the generic psychotic symptoms (hallucinations, disorganized thinking, delusions).

"While the 'normal' brain can distinguish the sound of a constantly dripping tap and relegate it as useless information, someone suffering from a psychosis cannot differentiate and will react equally to all environmental stimuli until the accumulative bombardment reaches a cacophony – they cannot habitualize to their surroundings. The most obvious path to regaining control is simply to 'scream' over at all.

"Assuming Roky suffered from such symptoms, his life as a rock musician – playing at extreme volume, using feedback to create a 'third sound,' would have addressed this dehabitualization. Equally, focusing on reciting lyrics, familiar information patterns, would have the same effect. While the relationship between LSD and psychosis is ultimately territory for the research scientist, it is particularly relevant to Roky's life. LSD's effects can stimulate the central nervous system to redefine its surroundings through a brand set of senses, and the result can be synaesthetic. A blue object in the real world is only reflecting light back into receptors in the eye to make it appear that color. In an altered state of perception the object could appear as a different color or stimulate another sense entirely – the color could be smelled or heard. The way in which hallucinogens influence dehabitualization validates the psychotic perception where the surroundings are 'emitting' too much information. In the Sixties, Roky coined the phrase 'I'm transmitting but not receiving,' which mirrored Nijinsky's anti-Descartian theory 'God is the fire in my head, I do not think and therefore I cannot go mad.' Historically there has always been rebellion in writers such as Baudelaire, Woolf and Poe, who chose their mental turmoil as a source of creation and the means of battling mundane normality..."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pgs. 81-82)

|

| Erickson |

Some have speculated that a certain drug he began taking leading up to his appearance before the draft board in 1966 played a much larger role in his psychosis than LSD. Taking this substance was part of a broader plan devised by Tommy Hall to help Roky beat the draft.

"Tommy and Clementine had always taken on a parental role in the relationship with Roky and decided to guide Roky through beating the draft board. Between them they constructed a plan that would require Roky to employ all of his skills as an actor while Tommy concocted an almost Gurdjieffian form of method acting for him. In his teaching, Gurdjieff set his pupils physical hurdles in order to overcome mental barriers. The idea was for Rocky to complain of back pains while presenting a suitably disoriented and disheveled appearance to support his suffering. Tommy used Asthmador as part of Roky's draft avoidance regimen. This was an asthma relief preparation that contained the active ingredient Atropine, a psychoactive compound present in both mandrake root and belladonna. Asthmador either came in powdered form, which was supposed to be lit and inhaled to clear bronchia, but could be misused by placing it in gelatin caps and swallowed. It also came in cigarette form in an unintentionally psychedelic red and green packet.

"Belladonna has had magical powers attributed to it since the Dark Ages, and its use as a poison is well known, but it had also been discovered as a drugstore high in the Sixties. Leary is reported to have stated that he'd never heard of a good belladonna trip. Atropine is the same substance present in Mandrax (from the mandrake root), which was heavily abused by Pink Floyd's madcap leader Syd Barrett and has often been attributed to the final crack in his sanity..."

(Eye Mind, Pal Drummond, pg. 171)

|

| Asthmador |

While Roky's mental state has generally been attributed to excessive drug use, many friends and associates of the Elevators have insisted that Roky's early psychosis was largely an act. What really unhinged him was not the drugs (at least at first), but the electroshock treatment he has been subjected to over the course of his life. While many believe that Roky was only subjected to electroshock after he was sent to Rusk in 1969, his relationship with the treatment began earlier than this.

Both Tommy and Clementine Hall have insisted that after the second time Roky had taken acid they dropped him off at his house before the effects of the drug had warn off. Evelyn Erickson, Roky's mother, was understandably shocked and, according to the Halls, she immediately took him to the Austin State Hospital for treatment. Evelyn has long denied this account but Chet Helms also noted that he had encountered Roky in an institution before the Elevators began. Helms, as noted above, was a regular visitor at the Halls' house even after he moved out to California in 1963. Clementine Hall has gone even further with her claims, stating:

"I think it was the second time Roky got high with us. Evelyn was the one who decided he was out of his mind and needed to be hospitalized when he was high – she thought he was crazy, she refused to believe he was high. And Tommy and I had said 'please don't make us take you home, we don't think you're gonna be safe there.' 'Oh, of course I'll be safe with my mom!' 'What if she sees you like this?' 'She'll be fine.' And she had him committed! I do know that while he was high, he was subjected to shock treatment, and that was when the biggest damage was done."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 81)

If this account is true, it should certainly be factored in to Erickson's breakdown. Roky was also institutionalized briefly while he was in San Francisco as well (in both cases, and in many others, Tommy Hall came to break Roky out) and while there were plans to give him electroshock therapy then, they apparently fell through. Upon returning to Texas from San Francisco, Roky began to seek out psychiatric help in order to thwart the draft board. At this point he seems to have gained a most curious patron who would protect him for a time.

"Help also came from another mysterious character in the Austin scene, Dr. 'Crazy Harry' Hermon, would later come to Roky's rescue again. The thirty-six-year-old Austrian-born research psychologist was definitely an outsider and the polar opposite to the medical norm in Texas. His eccentric 'jet set' air, his advocation of unconventional therapies combined with his Federal license to prescribe LSD put him in direct contact with the Austin underground where he helped fight many draft causes on medical grounds."

(Eye Mind, Paul Drummond, pg. 203)While largely forgotten now, "Crazy Harry" Hermon was a major LSD proponent in the 1960s. He also reportedly had a keen interest in hypnotism and nude therapy. After he was run out of Austin in the late 1960s by local law enforcement he became a member of the mysterious "Neo-American Church", which proclaimed hallucinogens as a religious sacrament. The "church" was founded in 1966 by Arthur Kleps, an associate of Leary's during the Millbrook days. The famed LSD chemist Nick Sand served as an "alchemist" for the Neo-American Church" before departing to San Francisco with the likely US intelligence asset William Mellon Hitchcock (who, along with the Millbrook scene, were discussed in depth here).

|

| Hermon is the masked and restrained individual in the center |

Unfortunately, Drummond doesn't really explain what other rescue Hermon performed for Roky. He is only mentioned once more in Eye Mind, in a quote from Evelyn Erickson recounting Roky's legal woes in 1968 (which resulted in him being subjected to electroshock treatment in a Houston psychiatric hospital for a brief time as well). Apparently many of the local psychiatrists wanted to subject Roky to a more "intense" regiment of treatments, but Hermon briefly protected him. There relationship seems to have ended after Roky was living with one of Hermon's nurses for a week or so, and then simply walked away. Its possible Hermon's own legal woes also led to his break with Erickson (and Austin on the whole) as well.

Roky's luck was about to come to an end, and he was finally subjected to heavy electroshock therapy shortly after the Elevators dissolved. He was not the only member that would receive such treatments either. These and other fates shall be considered in the final installment of this series. Stay tuned.